Understanding the Process of Oil-to-Gas Conversion

Roadmap and Outline: How Oil-to-Gas Conversion Fits the Energy Transition

Oil-to-gas conversion has become a pivotal chapter in the broader story of the energy transition. For many operators, it is a practical way to achieve immediate emissions reductions, improve local air quality, and streamline maintenance, all while preparing for a future where molecules and electrons work together more intelligently. In some settings, conversion is a bridge to full electrification; in others, it is a durable platform that can later accept low-carbon gases, carbon capture, or hydrogen blends. The key is understanding where natural gas excels, where it falls short, and how to execute a conversion that is efficient, compliant, and future-ready.

This article follows a clear path. We first establish the scope, constraints, and decision criteria that shape an oil-to-gas project. We then dive into the technical nuts and bolts of burners, boilers, controls, and fuel properties. Next, we examine emissions with both the direct combustion lens and the life-cycle perspective that includes methane leakage. We evaluate costs, risks, and policy signals that influence payback. Finally, we explore options to future-proof assets and conclude with guidance tailored to building owners, facility managers, and industrial teams.

Use this outline as your map:

– Why conversion matters now: security of supply, emissions, and operational reliability

– Technical foundations: equipment changes, safety, performance tuning, and standards

– Emissions accounting: combustion factors, methane management, local pollutants, and monitoring

– Economics and risk: capital costs, fuel and carbon prices, incentives, and resilience

– Future-ready choices: renewable gas, hydrogen blends, carbon capture, and electrification synergies

Two themes run throughout. First, the physics and chemistry are non-negotiable: natural gas typically emits around 20–30% less CO2 per unit of useful heat than comparable oil systems, while also slashing sulfur oxides and particulates. Second, context matters: a high-leakage supply chain or a rapidly decarbonizing electric grid can shift the decision. With that nuance in mind, the remaining sections bring data, examples, and practical tips so that your conversion is not only cleaner on paper but also robust in the field—more like replacing an old compass with a reliable GPS than simply repainting the map.

The Technical Core: From Oil Burners to Natural Gas Systems

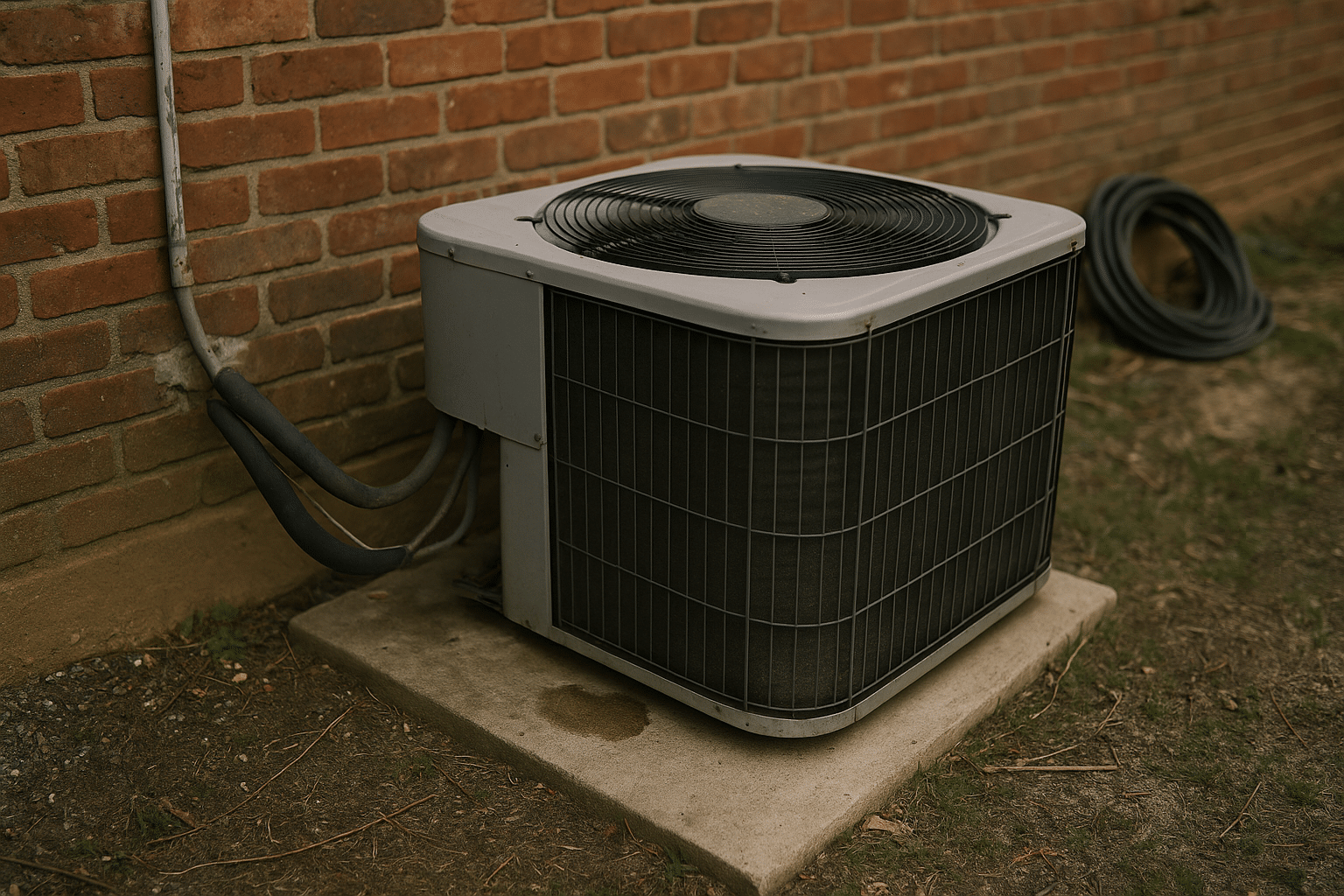

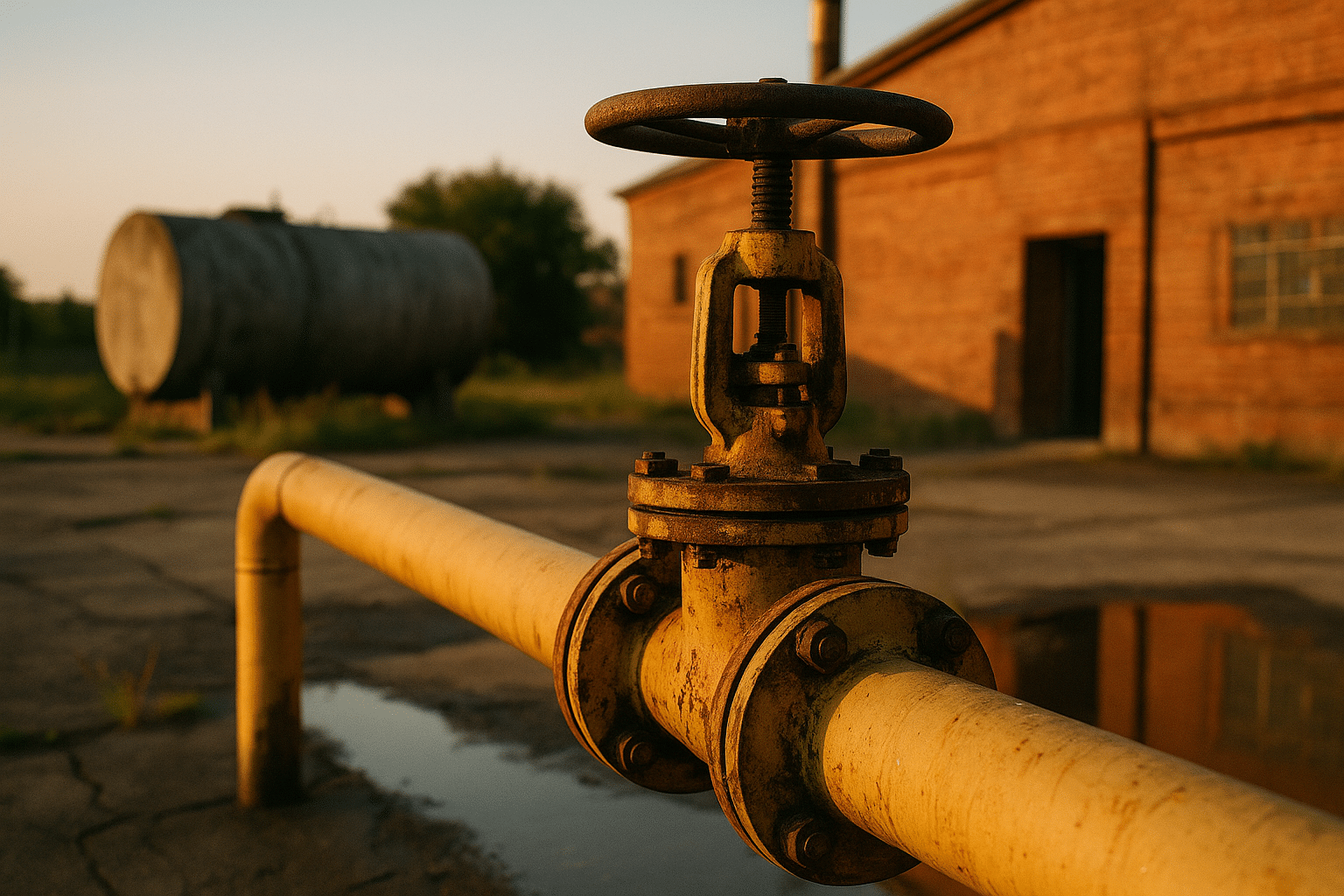

Oil-to-gas conversion is both a swap of fuel and a recalibration of heat-making hardware. Although every site is different, the conversion typically centers on three areas: burners and combustion controls, fuel delivery and metering, and safety systems. Unlike oil—which must be stored on-site, pumped, and often atomized for combustion—natural gas arrives via pipeline at regulated pressure, mixes more readily with air, and burns with cleaner characteristics that influence flame shape, heat transfer, and emissions.

Key equipment considerations include burner type (atmospheric, power, or ultra-low NOx), turndown ratio, and control logic. Gas burners usually offer finer modulation than legacy oil systems, supporting steadier loads and tighter temperature control. Proper air–fuel mixing is essential: too much excess air lowers efficiency and elevates NOx; too little risks incomplete combustion. Many projects also upgrade draft controls, oxygen trim, and variable-speed fans to optimize efficiency across the load curve. For boilers, heat exchanger surfaces may benefit from cleaning or reconfiguration because soot deposition—common with oil—declines markedly with gas, improving heat transfer and reducing maintenance.

Fuel delivery shifts from tank management to pipeline interconnection. That means verifying service line capacity, installing a meter, pressure regulator, and gas train with shutoff valves, pressure switches, and leakage tests. Safety is paramount: code-compliant venting, combustion air provisions, gas detection (where required), and lockout procedures reduce risk. Commissioning must include ignition control verification, flame safeguard tests, and a complete functional check at low and high fire. Equally important is documentation: as-built drawings, valve line-up diagrams, and maintenance schedules empower operators to keep performance steady over time.

A typical implementation sequence looks like this:

– Feasibility: load profiles, space constraints, and fuel availability

– Engineering: equipment sizing, gas train design, and code review

– Permitting: environmental approvals and utility coordination

– Installation: burner replacement, piping, controls integration, and venting

– Commissioning: combustion tuning, alarms testing, and performance verification

Performance outcomes hinge on careful tuning. Gas-fired units often achieve seasonal efficiencies in the 90–98% range for condensing designs and in the high 80s to low 90s for non-condensing configurations, while older oil systems may sit several points lower. That gap, combined with fewer fouling issues and longer maintenance intervals, translates into steadier output and reduced downtime. Think of it as changing from a carburetor to a fuel-injected engine: the physics of combustion become more controllable, and the system responds with smoother, cleaner heat.

Emissions Accounting: CO2, Methane, and Local Air Quality

The emissions case for oil-to-gas conversion is compelling at the point of combustion. Standard factors indicate that natural gas emits roughly 56 kg of CO2 per gigajoule of energy, heating oil about 74 kg/GJ, and coal approximately 94 kg/GJ. That implies a 20–30% reduction in direct CO2 when switching from oil to gas for the same useful heat, assuming similar efficiency. For a facility consuming 100,000 GJ annually, moving from oil to gas can cut about 1,800 metric tons of CO2 each year (a savings of 18 kg/GJ multiplied by 100,000 GJ), before accounting for efficiency gains or upstream effects.

Local pollutants tell a similar story. Gas contains negligible sulfur, which means sulfur dioxide drops to minimal levels after conversion. Particulate matter from fuel combustion largely disappears because gas burns without the ash and soot associated with oil. Nitrogen oxides typically fall, particularly with modern low-NOx burners and good control of excess air, although absolute NOx outcomes depend on firing conditions and technology selection. For communities downwind, these changes matter: reduced SO2 and PM improve local air quality and can help facilities comply with tightening standards.

The full picture, however, includes methane. Methane has a stronger warming effect than CO2—on the order of 80-plus times over 20 years and around 30 over 100 years—so leakage along the production and delivery chain can erode climate benefits. Observational studies have reported supply-chain leakage anywhere from roughly 1% to a few percent, with super-emitter events occasionally pushing higher in specific basins. Modeling shows that if leakage rises too high, short-term climate advantages narrow; conversely, robust leak detection and repair, better pneumatics, and swift remediation of abnormal releases preserve the advantage.

Practical takeaways include:

– Monitor and verify: request supplier disclosures on methane intensity or third-party certification

– Design for efficiency: higher seasonal efficiency means fewer upstream emissions per unit of delivered heat

– Tune for NOx: burner selection and oxygen trim can reduce NOx while safeguarding efficiency

– Track performance: continuous or periodic monitoring validates that expected reductions persist

When both direct combustion and realistic upstream controls are considered, oil-to-gas conversion remains a strong lever for near-term emissions and air quality improvements in many settings. It is most impactful where leakage is actively managed, where aging oil equipment is inefficient, and where the grid is not yet clean enough to support immediate full electrification at comparable life-cycle emissions and cost.

Costs, Payback, and Risk: Building a Resilient Business Case

Financially, oil-to-gas conversion blends upfront capital with operational savings. Capital items include burner replacements, gas train components, piping, controls integration, and venting modifications; some sites also require structural or ventilation changes. Soft costs—engineering, permitting, and commissioning—are equally important to budget. Fuel costs then shift from delivered oil to pipeline tariffs and commodity charges, with maintenance profiles often improving because gas combustion is cleaner and less prone to fouling.

Estimating payback requires a holistic view. Consider a hypothetical mid-size boiler plant that invests in a conversion valued at 500,000 units of local currency. If annual fuel savings amount to 120,000—driven by improved efficiency and a lower delivered energy price—and maintenance savings add 30,000, the simple payback is roughly 3.3 years. Carbon pricing, where applicable, can accelerate returns by monetizing avoided emissions. Conversely, if gas prices spike or connection capacity is limited, benefits can narrow or timelines stretch; sensitivity analysis helps managers see a range of outcomes.

A robust business case evaluates both measurable and contingent factors:

– Fuel price scenarios: compare multi-year ranges for oil and gas, not single points

– Efficiency deltas: document expected seasonal efficiency gains from tuning and controls

– Carbon and air regulations: account for current and likely future compliance costs

– Reliability: factor in reduced deliveries risk, especially in severe weather

– Flexibility: design for future low-carbon gas blends or carbon capture retrofit space

Risk management is as much about process as numbers. Early utility coordination confirms pressure and capacity; thorough engineering avoids undersized gas trains or venting bottlenecks; and commissioning with witnessed tests ensures that performance targets are met. Contracts can include performance guarantees for turndown, emissions, and efficiency. Finally, operator training preserves gains: even a well-designed system drifts without routine tuning, metering checks, and filter maintenance. In short, a strong financial case rests on careful scoping, disciplined execution, and a plan to keep the equipment at peak form after day one.

From Natural Gas to Net-Zero: Future-Ready Pathways and Conclusion

Natural gas can be a stepping stone toward deeper decarbonization if choices made today leave room for cleaner molecules and efficient electrification. Renewable natural gas—produced from landfills, wastewater, or agricultural digesters—can displace fossil supply with lower life-cycle intensity; in some cases, avoided methane from waste streams credits it with very low or even negative carbon intensity. Hydrogen blending is another path: modest blends by volume can be compatible with many modern appliances and networks, though energy content per unit volume drops and materials constraints must be respected. Planning space, interconnections, and controls with these trajectories in mind keeps options open.

Carbon capture is also moving from concept to practice on larger gas-fired assets. Post-combustion capture can cut the majority of CO2 at the stack, with an energy penalty that must be budgeted and heat integration that benefits from thoughtful plant design. For smaller sites, electrification may compete: high-efficiency heat pumps and thermal storage become attractive as grids decarbonize and as temperature requirements fit the technology envelope. Many portfolios will adopt a hybrid approach—leveraging gas for high-temperature, peaky, or backup loads while electrifying low-temperature baseloads as circuits and tariffs evolve.

Practical steps for future-proofing include:

– Specify low-NOx, high-modulation burners and advanced controls that support evolving fuels

– Reserve space and tie-in points for carbon capture or heat recovery retrofits

– Seek supply with demonstrated methane performance and consider renewable gas procurement

– Meter everything: submeter fuel, track stack O2 and NOx, and trend seasonal efficiency

– Revisit decisions periodically: as grid mixes, prices, and policies shift, re-optimize the asset

Conclusion for decision-makers: oil-to-gas conversion is a pragmatic move that reduces emissions now, tightens local air quality, and often improves operating economics. It is most effective when paired with credible methane management and a design that anticipates cleaner fuels and electrification where sensible. For building owners, this means lower maintenance and smoother heat; for industrial teams, it means reliable, controllable thermal energy that can integrate with future carbon solutions. Choose the project not just for year one, but for the pathway it enables—a runway from today’s reality to tomorrow’s low-carbon operations, without missing the safe landing in between.